skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Jomon art

The first settlers of Japan, the Jomon people (c 11000?–c 300 BC), named for the cord markings that decorated the surfaces of their clay vessels, were nomadic hunter-gatherers who later practiced organized farming and built cities with population of hundreds if not thousands. They built simple houses of wood and thatch set into shallow earthen pits to provide warmth from the soil. They crafted lavishly decorated pottery storage vessels, clay figurines called dogu, and crystal jewels.

The first settlers of Japan, the Jomon people (c 11000?–c 300 BC), named for the cord markings that decorated the surfaces of their clay vessels, were nomadic hunter-gatherers who later practiced organized farming and built cities with population of hundreds if not thousands. They built simple houses of wood and thatch set into shallow earthen pits to provide warmth from the soil. They crafted lavishly decorated pottery storage vessels, clay figurines called dogu, and crystal jewels.

Yayoi art

The next wave of immigrants was the Yayoi people, named for the district in Tokyo where remnants of their settlements first were found. These people, arriving in Japan about 350 BC, brought their knowledge of wetland rice cultivation, the manufacture of copper weapons and bronze bells (dotaku), and wheel-thrown, kiln-fired ceramics.

Kofun art

The third stage in Japanese prehistory, the Kofun, or Tumulus, period (c AD 250–552), represents a modification of Yayoi culture, attributable either to internal development or external force. In this period, diverse groups of people formed political alliances and coalesced into a nation. Typical artifacts are bronze mirrors, symbols of political alliances, and clay sculptures called haniwa which were erected outside tombs.

Asuka and Nara art

During the Asuka and Nara periods, so named because the seat of Japanese government was located in the Asuka Valley from 552 to 710 and in the city of Nara until 784, the first significant invasion by Asian continental culture took place in Japan.

During the Asuka and Nara periods, so named because the seat of Japanese government was located in the Asuka Valley from 552 to 710 and in the city of Nara until 784, the first significant invasion by Asian continental culture took place in Japan.

The transmission of Buddhism provided the initial impetus for contacts between China, Korea and Japan. The Japanese recognized the facets of Chinese culture that could profitably be incorporated into their own: a system for converting ideas and sounds into writing; historiography; complex theories of government, such as an effective bureaucracy; and, most important for the arts, new technologies, new building techniques, more advanced methods of casting in bronze, and new techniques and media for painting.

Throughout the 7th and 8th centuries, however, the major focus in contacts between Japan and the Asian continent was the development of Buddhism. Not all scholars agree on the significant dates and the appropriate names to apply to various time periods between 552, the official date of the introduction of Buddhism into Japan, and 784, when the Japanese capital was transferred from Nara. The most common designations are the Suiko period, 552–645; the Hakuho period, 645–710, and the Tenpyo period, 710–784.

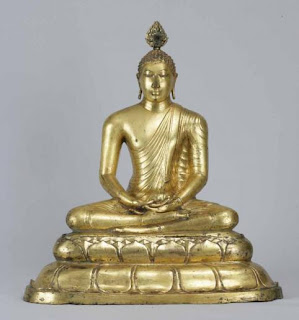

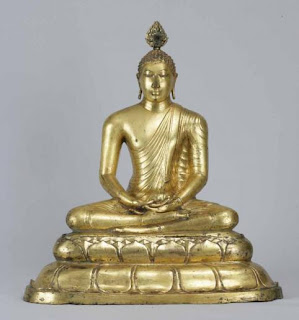

The earliest Japanese sculptures of the Buddha are dated to the 6th and 7th century.They ultimately derive from the 1st-3rd century CE Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara, characterized  by flowing dress patterns and realistic rendering, on which Chinese and Korean artistic traits were superimposed.These indigenous characteristics can be seen in early Buddhist art in Japan and some early Japanese Buddhist sculpture is now believed to have originated in Korea, particularly from Baekje, or Korean artisans who immigrated to Yamato Japan. Particularly, the semi-seated Maitreya form was adapted into a highly developed Korean style which was transmitted to Japan as evidenced by the Koryu-ji Miroku Bosatsu and the Chugu-ji Siddhartha statues. Although many historians portray Korea as a mere transmitter of Buddhism, the Three Kingdoms, and particularly Baekje, were instrumental as active agents in the introduction and formation of a Buddhist tradition in Japan in 538 or 552. They illustrate the terminal point of the Silk Road transmission of Art during the first few centuries of our era. Other examples can be found in the development of the iconography of the Japanese Fujin Wind God, the Nio guardians, and the near-Classical floral patterns in temple decorations.

by flowing dress patterns and realistic rendering, on which Chinese and Korean artistic traits were superimposed.These indigenous characteristics can be seen in early Buddhist art in Japan and some early Japanese Buddhist sculpture is now believed to have originated in Korea, particularly from Baekje, or Korean artisans who immigrated to Yamato Japan. Particularly, the semi-seated Maitreya form was adapted into a highly developed Korean style which was transmitted to Japan as evidenced by the Koryu-ji Miroku Bosatsu and the Chugu-ji Siddhartha statues. Although many historians portray Korea as a mere transmitter of Buddhism, the Three Kingdoms, and particularly Baekje, were instrumental as active agents in the introduction and formation of a Buddhist tradition in Japan in 538 or 552. They illustrate the terminal point of the Silk Road transmission of Art during the first few centuries of our era. Other examples can be found in the development of the iconography of the Japanese Fujin Wind God, the Nio guardians, and the near-Classical floral patterns in temple decorations.

The earliest Buddhist structures still extant in Japan, and the oldest wooden buildings in the Far East are found at the Horyu-ji to the southwest of Nara. First built in the early 7th century as the private temple of Crown Prince Shotoku, it consists of 41 independent buildings. The most important ones, the main worship hall, or Kondo (Golden Hall), and Goju-no-to (Five-story Pagoda), stand in the center of an open area surrounded by a roofed cloister. The Kondo, in the style of Chinese worship halls, is a two-story structure of post-and-beam construction, capped by an irimoya, or hipped-gabled roof of ceramic tiles.

Japanese art

covers a wide range of art styles and media, including ancient pottery, sculpture in wood and bronze, ink painting on silk and paper, and a myriad of other types of works of art. It also has a long history, ranging from the beginnings of human habitation in Japan, sometime in the 10th millennium BC, to the present.

Historically, Japan has been subject to sudden invasions of new and alien ideas followed by long periods of minimal contact with the outside world. Over time the Japanese developed the ability to absorb, imitate, and finally assimilate those elements of foreign culture that complemented their aesthetic preferences. The earliest complex art in Japan was produced in the 7th and 8th centuries A.D. in connection with Buddhism. In the 9th century, as the Japanese began to turn away from China and develop indigenous forms of expression, the secular arts became increasingly important; until the late 15th century, both religious and secular arts flourished. After the Onin War (1467-1477), Japan entered a period of political, social, and economic disruption that lasted for over a century. In the state that emerged under the leadership of the Tokugawa shogunate, organized religion played a much less important role in people's lives, and the arts that survived were primarily secular.

Painting is the preferred artistic expression in Japan, practiced by amateurs and professionals alike. Until modern times, the Japanese wrote with a brush rather than a pen, and their familiarity with brush techniques has made them particularly sensitive to the values and aesthetics of painting. With the rise of popular culture in the Edo period, a style of woodblock prints called ukiyo-e became a major art form and its techniques were fine tuned to produce colorful prints of everything from daily news to schoolbooks. The Japanese, in this period, found sculpture a much less sympathetic medium for artistic expression; most Japanese sculpture is associated with religion, and the medium's use declined with the lessening importance of traditional Buddhism.

The museum's collection

History

The museum came into being in 1872, when the first exhibition was held by the Museum Department of the Ministry of Education at the Taiseiden Hall. This marked the inauguration of the first museum in Japan. Soon after the opening, the museum moved to Uchiyamashita-cho (present Uchisaiwai-cho), then in 1882 moved again to the Ueno Park, where it stands today. Since its establishment, the museum has experienced major challenges such as the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923, and a temporary closing in 1945, during World War II. In more than the 120 years of its history, the museum has gone under much evolution and transformation through organizational reforms and administrative change.

The museum went through several name changes, being called the Imperial Museum in 1886 and the Tokyo Imperial Household Museum in 1900, until it was given its present title in 1947.

Honkan (Japanese Gallery)

The original Main Gallery (designed by the British architect Josiah Conder) was severely damaged in the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923. In contrast to the original building's more Western style, the design of the present Honkan by Watanabe Jin is the more eastern "emperor's crown style". Construction began in 1932, and the building was inaugurated in 1938. It was designated an Important Cultural Property of Japan in 2001.

The Japanese Gallery provides a general view of Japanese art, containing 24 exhibition rooms on two floors. It consists of exhibitions from 10,000 B.C. up to the late 19th century, exhibitions of different types of art such as ceramics, sculpture, swords, and others.

- The 1st room - The 10th room (2F): The title is "The flow of Japanese art". It interlaces theme exhibitions such as "Art of Buddhism", "Art of Tea ceremony", "The clothing of Samurai", "Noh and Kabuki", and etc. One national treasure object is exhibited by turns every time in the 2nd room as "The national treasure room".

- The 11th room - The 20th room (1F): There are exhibition rooms according to the genres such as Sculpture, Metalworking, Pottery, Japanning, Katana, Ethnic material, Historic material, Modern art, and etc.

- The extra exhibition rooms (1F and 2F): There are small exhibition rooms where planning such as "new objects exhibitions".

- The extra room (1F): This is an event meeting place for children.

Toyokan (Asian Gallery)

This building was inaugurated in 1968 and designed by Taniguchi Yoshio. This is a three-storied building which bring a feeling such as five-storied. Because there are large floors arranged in a spiral ascending from the 1st floor along the mezzanines to the 3rd floor, and many stairs. It has been made huge colonnade air space to reach from the first floor to the third floor ceiling inside, and placement of an exhibition room is complicated. There is a restaurant and museum shop on the first floor, too.

The Asian Gallery consists of ten exhibition rooms arranged on seven region levels. It is dedicated to the art and archaeology of Asia, including China, the Korean peninsula, Southeast Asia, India, the Middle east and Egypt.

- The 1st room (1F): Sculptures of India and Gandhara in Pakistan.

- The 2nd and 3rd room (1F): Egypt, West Asia, Southeast Asia, and South Asia.

- he 4th and 5th room (2F): Chinese artifacts and archaeologiy.

- The 6th and 7th room (2F): Lounge and Small exhibit space.

- The 8th room (2F): Chinese painting and calligraphy.

- The 9th and 10th room (3F): Central Asia and Korean peninsula.

Hyokeikan

Built to commemorate the marriage of the then Meiji Crown Prince (later Emperor Taisho), Hyokeikan was inaugurated in 1909. This building is designated as an Important Cultural Property as a representative example of Western-style architecture of the late Meiji period (early 20th century). It is open for events and temporary exhibitions only.

Heiseikan

Heiseikan serves primarily as space for special exhibitions, but also houses the Japanese Archaeology Gallery. The Japanese Archaeology Gallery on the first floor traces Japanese history from ancient to pre-modern times through archaeological objects. The galleries on the second floor are entirely dedicated to special exhibitions. The Heiseikan building was opened in 1999 to commemorate the crown prince's marriage. The building also contains an auditorium and lounge area.

This gallery displays some examples of pottery, the Jomon linear appliqué type, from around 10,000 BC. The antiquity of these potteries was first identified after World War II, through radiocarbon dating methods: "The earliest pottery, the linear applique type, was dated by radiocarbon methods taken on samples of carbonized material at 12500 +- 350 before present" (Prehistoric Japan, Keiji Imamura).

Japanese museums

was introduced to the idea of Western-style museums (hakubutsukan) as early as the Bakumatsu period through Dutch Studies. Upon the conclusion of the US-Japan Amity Treaty in 1858, a Japanese delegation to America observed Western-style museums first-hand.Following the Meiji Restoration, botanist Itou Keisuke, and natural historian, Tanaka Yoshio, also wrote of the necessity of establishing museum facilities similar to the ones found in the West. Preparations commenced to construct facilities to preserve historical relics of the past.In 1871, the Museum of the Ministry of Education (Monbusho Hakubutsukan) staged Japan’s first exhibition in the Yushima area of Tokyo. Minerals, fossils, animals, plants, regional crafts, and artifacts were among the articles displayed.Following the Yushima exposition, the government set up a bureau charged with the construction of a permanent museum. The bureau proposed that in keeping with Japan’s participation in the Vienna World Fair of 1873, a Home Ministry Museum (now, the Tokyo National Museum) eventually be developed.In 1877, the Museum of Education (Kyoiku Hakubutsukan)opened in Ueno Park (now, the National Science Museum of Japan) with displays devoted to physics, chemistry, zoology, botany, and regional crafts. As a part of the exhibition, art objects were also displayed in an “art museum.”The Imperial Household Department oversaw the establishment of a central museum dedicated to historical artifacts in 1886. In addition, in the years after 1877, there was great enthusiasm for establishing regional museums in Akita, Niigata, Kanazawa, Kyoto, Osaka, and Hiroshima.In 1895, the Nara National Museum opened its doors, followed in 1897 by the Kyoto National Museum. Other national specialty museums followed: the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce Exhibition Hall (1897), Patent Office Exhibition Hall (1905), and the Postal Museum (1902).In addition to the national museums, private museums were also established after the turn of the century. The first private museum was the Okura Shukokan Museum, built in 1917 to house Okura Kihachiro’s collection. The industrialist Ôhara Mogasaburo established the Ôhara Museum of Art in 1930 in Kurashiki, Okayama Prefecture. The museum was the first Japanese museum devoted to Western art. Private museums continued to open after the war. In 1966, the Yamatane Museum of Art and the Idemitsu Art Gallery, both built around private collections, were established.By 1945, there were 150 museums in Japan. However, the Great Kanto Earthquake (1923), the Sino-Japanese war, and World War II, led to the stagnation of Japan’s museum activities.Plans for museums that had been put on hold during the war recommenced in the 1950s. The Kyoiku Hakubutsukan became the National Science Museum of Japan (Kokuritsu Kagaku Hakubutsukan)in 1949, and the former Monbusho Hakubutsukan became the Tokyo National Museum (Tokyo Kokuritsu Hakubutsukan)in 1952.Japanese art objects had been collected in the Shôsôin (treasure houses) of shrines and temples from the Nara Period on. Artifacts were included in the national hakubutsukan established during the Meiji period, but were not assigned to the distinct category of art museum (bijutsukan) until after 1945.Tokyo National Museum

was introduced to the idea of Western-style museums (hakubutsukan) as early as the Bakumatsu period through Dutch Studies. Upon the conclusion of the US-Japan Amity Treaty in 1858, a Japanese delegation to America observed Western-style museums first-hand.Following the Meiji Restoration, botanist Itou Keisuke, and natural historian, Tanaka Yoshio, also wrote of the necessity of establishing museum facilities similar to the ones found in the West. Preparations commenced to construct facilities to preserve historical relics of the past.In 1871, the Museum of the Ministry of Education (Monbusho Hakubutsukan) staged Japan’s first exhibition in the Yushima area of Tokyo. Minerals, fossils, animals, plants, regional crafts, and artifacts were among the articles displayed.Following the Yushima exposition, the government set up a bureau charged with the construction of a permanent museum. The bureau proposed that in keeping with Japan’s participation in the Vienna World Fair of 1873, a Home Ministry Museum (now, the Tokyo National Museum) eventually be developed.In 1877, the Museum of Education (Kyoiku Hakubutsukan)opened in Ueno Park (now, the National Science Museum of Japan) with displays devoted to physics, chemistry, zoology, botany, and regional crafts. As a part of the exhibition, art objects were also displayed in an “art museum.”The Imperial Household Department oversaw the establishment of a central museum dedicated to historical artifacts in 1886. In addition, in the years after 1877, there was great enthusiasm for establishing regional museums in Akita, Niigata, Kanazawa, Kyoto, Osaka, and Hiroshima.In 1895, the Nara National Museum opened its doors, followed in 1897 by the Kyoto National Museum. Other national specialty museums followed: the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce Exhibition Hall (1897), Patent Office Exhibition Hall (1905), and the Postal Museum (1902).In addition to the national museums, private museums were also established after the turn of the century. The first private museum was the Okura Shukokan Museum, built in 1917 to house Okura Kihachiro’s collection. The industrialist Ôhara Mogasaburo established the Ôhara Museum of Art in 1930 in Kurashiki, Okayama Prefecture. The museum was the first Japanese museum devoted to Western art. Private museums continued to open after the war. In 1966, the Yamatane Museum of Art and the Idemitsu Art Gallery, both built around private collections, were established.By 1945, there were 150 museums in Japan. However, the Great Kanto Earthquake (1923), the Sino-Japanese war, and World War II, led to the stagnation of Japan’s museum activities.Plans for museums that had been put on hold during the war recommenced in the 1950s. The Kyoiku Hakubutsukan became the National Science Museum of Japan (Kokuritsu Kagaku Hakubutsukan)in 1949, and the former Monbusho Hakubutsukan became the Tokyo National Museum (Tokyo Kokuritsu Hakubutsukan)in 1952.Japanese art objects had been collected in the Shôsôin (treasure houses) of shrines and temples from the Nara Period on. Artifacts were included in the national hakubutsukan established during the Meiji period, but were not assigned to the distinct category of art museum (bijutsukan) until after 1945.Tokyo National Museum

Established 1872, the Tokyo National Museum (Tokyo Kokuritsu Hakubutsukan), or TNM, is the oldest and largest museum in Japan. The museum collects, houses, and preserves a comprehensive collection of art works and archaeological objects of Asia, focusing on Japan. The museum holds over 110,000 objects, which includes 87 Japanese National Treasure holdings and 610 Important Cultural Property holdings (as of July, 2005). The museum also conducts research and organizes educational events related to its collection.The museum is located inside Ueno Park in Taito, Tokyo. The facilities consist of the Honkan (, Japanese Gallery), Toyokan (, Asian Gallery), Hyokeikan, Heiseikan, Horyu-ji Homotsukan (the Gallery of Horyu-ji Treasures), as well as Shiryokan (, the Research and Information Center) and other facilities (Map). There are restaurants and shops within the museum's premises, as well as outdoor exhibitions and a garden where visitors can enjoy seasonal views.HistoryThe museum came into being in 1872, when the first exhibition was held by the Museum Department of the Ministry of Education at the Taiseiden Hall. This marked the inauguration of the first museum in Japan. Soon after the opening, the museum moved to Uchiyamashita-cho (present Uchisaiwai-cho), then in 1882 moved again to the Ueno Park, where it stands today. Since its establishment, the museum has experienced major challenges such as the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923, and a temporary closing in 1945, during World War II. In more than the 120 years of its history, the museum has gone under much evolution and transformation through organizational reforms and administrative change.The museum went through several name changes, being called the Imperial Museum in 1886 and the Tokyo Imperial Household Museum in 1900, until it was given its present title in 1947.

Established 1872, the Tokyo National Museum (Tokyo Kokuritsu Hakubutsukan), or TNM, is the oldest and largest museum in Japan. The museum collects, houses, and preserves a comprehensive collection of art works and archaeological objects of Asia, focusing on Japan. The museum holds over 110,000 objects, which includes 87 Japanese National Treasure holdings and 610 Important Cultural Property holdings (as of July, 2005). The museum also conducts research and organizes educational events related to its collection.The museum is located inside Ueno Park in Taito, Tokyo. The facilities consist of the Honkan (, Japanese Gallery), Toyokan (, Asian Gallery), Hyokeikan, Heiseikan, Horyu-ji Homotsukan (the Gallery of Horyu-ji Treasures), as well as Shiryokan (, the Research and Information Center) and other facilities (Map). There are restaurants and shops within the museum's premises, as well as outdoor exhibitions and a garden where visitors can enjoy seasonal views.HistoryThe museum came into being in 1872, when the first exhibition was held by the Museum Department of the Ministry of Education at the Taiseiden Hall. This marked the inauguration of the first museum in Japan. Soon after the opening, the museum moved to Uchiyamashita-cho (present Uchisaiwai-cho), then in 1882 moved again to the Ueno Park, where it stands today. Since its establishment, the museum has experienced major challenges such as the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923, and a temporary closing in 1945, during World War II. In more than the 120 years of its history, the museum has gone under much evolution and transformation through organizational reforms and administrative change.The museum went through several name changes, being called the Imperial Museum in 1886 and the Tokyo Imperial Household Museum in 1900, until it was given its present title in 1947.

Japanese festivalsJapanese festivals are traditional festive occasions. Some festivals have their roots in Chinese festivals but have undergone dramatic changes as they mixed with local customs.These Japanese festival has deep root in Nepal.Concept of these festivals transported to China from Nepal then from China to Japan. Nepal has same festival as in Japan till today like Machendra Jatra, Indra Jatra. Some are so different that they do not even remotely resemble the original festival despite sharing the same name and date. There are also various local festivals (e.g. Tobata Gion) that are mostly unknown outside a given prefecture. It is commonly said that you will always find a festival somewhere in Japan. Unlike most people of East Asian descent, Japanese people generally do not celebrate Chinese New Year (it having been supplanted by the Western New Year's Day in the late 19th century); although Chinese residents in Japan still do. In Yokohama Chinatown, Japan's biggest Chinatown, tourists from all over Japan come to enjoy the festival. And similarly the Nagasaki Lantern Festival is based in Nagasaki's China town. See: Japanese New Year.Local festivals (Matsuri)Matsuri is the Japanese word for a festival or holiday. In Japan, festivals are usually sponsored by a local shrine or temple, though they can be secular.  There is no specific matsuri days for all of Japan; dates vary from area to area, and even within a specific area, but festival days do tend to cluster around traditional holidays such as Setsubun or Obon. Almost every locale has at least one matsuri in late summer/early autumn, usually related to the rice harvest. Notable matsuri often feature processions which may include elaborate floats. Preparation for these processions is usually organized at the level of neighborhoods, or machi. Prior to these, the local kami may be ritually installed in mikoshi and paraded through the streets. One can always find in the vicinity of a matsuri booths selling souvenirs and food such as takoyaki, and games, such as Goldfish scooping. Karaoke contests, sumo matches, and other forms of entertainment are often organized in conjunction with matsuri. If the festival is next to a lake, renting a boat is also an attraction.New Year

There is no specific matsuri days for all of Japan; dates vary from area to area, and even within a specific area, but festival days do tend to cluster around traditional holidays such as Setsubun or Obon. Almost every locale has at least one matsuri in late summer/early autumn, usually related to the rice harvest. Notable matsuri often feature processions which may include elaborate floats. Preparation for these processions is usually organized at the level of neighborhoods, or machi. Prior to these, the local kami may be ritually installed in mikoshi and paraded through the streets. One can always find in the vicinity of a matsuri booths selling souvenirs and food such as takoyaki, and games, such as Goldfish scooping. Karaoke contests, sumo matches, and other forms of entertainment are often organized in conjunction with matsuri. If the festival is next to a lake, renting a boat is also an attraction.New Year nformation: New Year observances are the most important and elaborate of Japan's annual events. Before the New Year, homes are cleaned, debts are paid off, and osechi (food in lacquered trays for the New Year) is prepared or bought. Osechi foods are traditional foods which are chosen for their lucky colors, shapes, or lucky-sounding names in hopes of obtaining good luck in various areas of life during the new year. Homes are decorated and the holidays are celebrated by family gatherings, visits to temples or shrines, and formal calls on relatives and friends. The first day of the year (ganjitsu) is usually spent with members of the family.

nformation: New Year observances are the most important and elaborate of Japan's annual events. Before the New Year, homes are cleaned, debts are paid off, and osechi (food in lacquered trays for the New Year) is prepared or bought. Osechi foods are traditional foods which are chosen for their lucky colors, shapes, or lucky-sounding names in hopes of obtaining good luck in various areas of life during the new year. Homes are decorated and the holidays are celebrated by family gatherings, visits to temples or shrines, and formal calls on relatives and friends. The first day of the year (ganjitsu) is usually spent with members of the family.

People try to stay awake and eat toshikoshisoba, which is soba noodles that would be eaten to at midnight. People also visit Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines. Traditionally three shrines or temples are visited. This is called sansha-mairi. In the Imperial Palace at dawn on the 1st of January, the emperor performs the rite of shihohai(worship of the four quarters), in which he does reverence in the direction of various shrines and imperial tombs and offers prayers for the well-being of the nation. On January 2 the public is allowed to enter the inner palace grounds; the only other day this is possible is the emperor's birthday (December 23). On the 2nd and 3rd days acquaintances visit one another to extend greetings (nenshi) and sip otoso (a spiced rice wine). Some games played at New Year's are karuta (a card game), hanetsuki (similar to badminton), tako age (kiteflying), and komamawashi (spinning tops). These games are played to bring more luck for the year. Exchanging New Year's greeting cards (similar to Christmas Cards in Western countries) is another important Japanese custom. Also special allowances are given to children, which are called otoshidama. They also decorate their entrances with kagami-mochi (2 mochi rice balls placed one on top of the other, with a tangerine on top), and kadomatsu (pine tree decorations).

A later New Year's celebration, Koshogatsu, literally means "Small New Year" and starts with the first full moon of the year (around January 15). The main events of Koshogatsu are rites and practices praying for a bountiful harvest

Doll FestivalOther Names: Sangatsu Sekku (3rd month Festival), Momo Sekku (Peach Festival), Joshi no Sekku (Girls' Festival) This is the day families pray for the happiness and prosperity of their girls and to help ensure that they grow up healthy and beautiful. The celebration takes place both inside the home and at the seashore. Both parts are meant to ward off evil spirits from girls. Young girls put on their best kimonos and visit their friends' homes. Tiered platforms for hina ningyo (hina dolls; a set of dolls representing the emperor, empress, attendants, and musicians in ancient court dress) are set up in the home, and the family celebrates with a special meal of hishimochi (diamond-shaped rice cakes) and shirozake (rice malt with sake).HanamiOther Names: Hanami (flower viewing), Cherry Blossom FestivalInformation: Various flower festivals are held at Shinto shrines during the month of April. Excursions and picnics for enjoying flowers, particularly cherry blossoms are also common. In some places flower viewing parties are held on traditionally fixed dates. This is one of the most popular events during spring. The subject of flower viewing has long held an important place in literature, dance and the fine arts. Ikebana (flower arrangement) is also a popular part of Japanese culture and is still practiced by many people today. Some main things people do during this event are: games, folk songs, folk dance, flower displays, rides, parades, concerts, kimono shows, booths with food and other things, beauty pageant, and religious ceremonies.

This is the day families pray for the happiness and prosperity of their girls and to help ensure that they grow up healthy and beautiful. The celebration takes place both inside the home and at the seashore. Both parts are meant to ward off evil spirits from girls. Young girls put on their best kimonos and visit their friends' homes. Tiered platforms for hina ningyo (hina dolls; a set of dolls representing the emperor, empress, attendants, and musicians in ancient court dress) are set up in the home, and the family celebrates with a special meal of hishimochi (diamond-shaped rice cakes) and shirozake (rice malt with sake).HanamiOther Names: Hanami (flower viewing), Cherry Blossom FestivalInformation: Various flower festivals are held at Shinto shrines during the month of April. Excursions and picnics for enjoying flowers, particularly cherry blossoms are also common. In some places flower viewing parties are held on traditionally fixed dates. This is one of the most popular events during spring. The subject of flower viewing has long held an important place in literature, dance and the fine arts. Ikebana (flower arrangement) is also a popular part of Japanese culture and is still practiced by many people today. Some main things people do during this event are: games, folk songs, folk dance, flower displays, rides, parades, concerts, kimono shows, booths with food and other things, beauty pageant, and religious ceremonies.

Boy's Day (Kodomo no hi)Other Names: Iris Festival (Shobu no Sekku), Tango Festival (Tango no Sekku)Information: May is the month of the Iris Festival. The tall-stemmed Japanese iris is a symbolic flower. Its long, narrow leaves resemble the sharp blades off a sword, and for many centuries it has been the custom to place iris leaves in a boy's bath to give him a martial spirit. Originally May 5 was a festival for boys corresponding to the Doll Festival, for girls, but in 1948 it was renamed Children's Day, and made a national holiday. However, this might be a misnomer; the symbols of courage and strength mainly honor boys. It is customary on this day for families with male children to fly koinobori (carp streamers, a symbol of success) outside the house, display warrior dolls (musha ningyo) inside, and eat chimaki (rice cakes wrapped in cogan grass or bamboo leaves) and kashiwamochi (rice cakes filled with bean paste and wrapped in oak leaves). Also known as kodomo no hi

Boy's Day (Kodomo no hi)Other Names: Iris Festival (Shobu no Sekku), Tango Festival (Tango no Sekku)Information: May is the month of the Iris Festival. The tall-stemmed Japanese iris is a symbolic flower. Its long, narrow leaves resemble the sharp blades off a sword, and for many centuries it has been the custom to place iris leaves in a boy's bath to give him a martial spirit. Originally May 5 was a festival for boys corresponding to the Doll Festival, for girls, but in 1948 it was renamed Children's Day, and made a national holiday. However, this might be a misnomer; the symbols of courage and strength mainly honor boys. It is customary on this day for families with male children to fly koinobori (carp streamers, a symbol of success) outside the house, display warrior dolls (musha ningyo) inside, and eat chimaki (rice cakes wrapped in cogan grass or bamboo leaves) and kashiwamochi (rice cakes filled with bean paste and wrapped in oak leaves). Also known as kodomo no hi

Tanabata

Tanabata

Other Names: The Star Festival

Information: It originated from a Chinese folk legend concerning two stars-the Weaver Star (Vega) and the Cowherd Star (Altair)-who were said to be lovers who could meet only once a year on the 7th night of the 7th month provided it didn't rain and flood the Milky Way. It was named Tanabata after a weaving maiden from a Japanese legend who was believed to make clothes for the gods. People often write wishes and romantic aspirations on long, narrow strips of coloured paper and hang them on bamboo branches along with other small ornaments.

Bon Festival

Information: A Buddhist observance honoring the spirits of ancestors. Usu ally a "spirit altar" (shoryodana) is set up in front of the Butsudan (buddhist family altar) to welcome the ancestors' souls. A priest is usually asked to come and read a sutra (tanagyo). Among the traditional preparations for the ancestors' return are the cleaning of grave sites and preparing a path from them to the house and the provision of straw horses or oxen for the ancestors' transportation. The welcoming fire (mukaebi) built on the 13th and the send-off fire (okuribi) built on the 16th are intended to light the path.

ally a "spirit altar" (shoryodana) is set up in front of the Butsudan (buddhist family altar) to welcome the ancestors' souls. A priest is usually asked to come and read a sutra (tanagyo). Among the traditional preparations for the ancestors' return are the cleaning of grave sites and preparing a path from them to the house and the provision of straw horses or oxen for the ancestors' transportation. The welcoming fire (mukaebi) built on the 13th and the send-off fire (okuribi) built on the 16th are intended to light the path.

Popular cultureJapanese popular culture not only reflects the attitudes and concerns of the present but also provides a link to the past. Popular films, television programs, Manga, and mus ic all developed from older artistic and literary traditions, and many of their themes and styles of presentation can be traced to traditional art forms. Contemporary forms of popular culture, much like the traditional forms, provide not only entertainment but also an escape for the contemporary Japanese from the problems of an industrial world. When asked how they spent their leisure time, 80 percent of a sample of men and women surveyed by the government in 1986 said they averaged about two and one-half hours per weekday watching television, listening to the radio, and reading newspapers or magazines. Some 16 percent spent an average of two and one-quarter hours a day engaged in hobbies or amusements. Others spent leisure time participating in sports, socializing, and personal study. Teenagers and retired people reported more time spent on all of these activities than did other groups.

ic all developed from older artistic and literary traditions, and many of their themes and styles of presentation can be traced to traditional art forms. Contemporary forms of popular culture, much like the traditional forms, provide not only entertainment but also an escape for the contemporary Japanese from the problems of an industrial world. When asked how they spent their leisure time, 80 percent of a sample of men and women surveyed by the government in 1986 said they averaged about two and one-half hours per weekday watching television, listening to the radio, and reading newspapers or magazines. Some 16 percent spent an average of two and one-quarter hours a day engaged in hobbies or amusements. Others spent leisure time participating in sports, socializing, and personal study. Teenagers and retired people reported more time spent on all of these activities than did other groups. Many anime and manga are becoming very popular around the world, as well as Japanese video games, music, and game shows, this has made Japan an "entertainment superpower" along with the United States and European Union.In the late 1980s, the family was the focus of leisure activities, such as excursions to parks or shopping districts. Although Japan is often thought of as a hard-working society with little time for leisure, the Japanese seek entertainment wherever they can. It is common to see Japanese commuters riding the train to work, enjoying their favorite manga, or listening through earphones to the latest in popular music on portable music players.A wide variety of types of popular entertainment are available. There is a large selection of music, films, and the products of a huge comic book industry, among other forms of entertainment, from which to choose. Game centers, bowling alleys, and karaoke are popular hangout places for teens while older people may play shogi or go in specialized parlors.

Many anime and manga are becoming very popular around the world, as well as Japanese video games, music, and game shows, this has made Japan an "entertainment superpower" along with the United States and European Union.In the late 1980s, the family was the focus of leisure activities, such as excursions to parks or shopping districts. Although Japan is often thought of as a hard-working society with little time for leisure, the Japanese seek entertainment wherever they can. It is common to see Japanese commuters riding the train to work, enjoying their favorite manga, or listening through earphones to the latest in popular music on portable music players.A wide variety of types of popular entertainment are available. There is a large selection of music, films, and the products of a huge comic book industry, among other forms of entertainment, from which to choose. Game centers, bowling alleys, and karaoke are popular hangout places for teens while older people may play shogi or go in specialized parlors.

Traditional Japanese architecture

Japanese architecture has as long a history as any other aspect of Japanese culture. Originally heavily influenced by Chinese architecture, it also develops many differences and aspects which are indigenous to India. Examples of traditional architecture are seen at Temples, Shinto shrines and castles in Kyoto, and Nara. Some of these buildings are constructed with traditional gardens, which are influenced from Zen ideas.

Japanese architecture has as long a history as any other aspect of Japanese culture. Originally heavily influenced by Chinese architecture, it also develops many differences and aspects which are indigenous to India. Examples of traditional architecture are seen at Temples, Shinto shrines and castles in Kyoto, and Nara. Some of these buildings are constructed with traditional gardens, which are influenced from Zen ideas.

Some modern architects, such as Yoshio Taniguchi and Tadao Ando are known for their amalgamation of Japanese traditional and Western architectural influences.

Traditional Japanese architecture has been highly affected since Japan decided to open its gates to western culture and architecture in particular. Japan made efforts to preserve traditional Japanese architecture features, but western modern architecture has taken its tole and now we see more concrete and steel and flat-roofs terraces in modern Japanese houses.

Japanese houses are usually built on three floors, no cellars or basements. They use wooden floors and sliding doors and windows. Japanese homes have very small bathrooms, which are limited to the bath and shower space. Big cities in Japan are very crowded; therefore, Japanese homes rarely have a garden.

Japanese houses are usually built on three floors, no cellars or basements. They use wooden floors and sliding doors and windows. Japanese homes have very small bathrooms, which are limited to the bath and shower space. Big cities in Japan are very crowded; therefore, Japanese homes rarely have a garden.

The summer season in Japan is quite rainy and humid. So, in order to keep Japanese homes airy and cool, most Japanese houses are built from thin timber walls and have slanted, slightly curved roofs. That is why Japanese home architecture is more likely to suffer from earthquakes and fires.

Japanese culture is based on aesthetics and the natural environment. Its ideas of balance, harmony, economy and beauty are projected in Japanese art and architecture, for example: traditional Japanese houses, the art of flower arrangement, brush painting and the famous Japanese tea ceremony.

Clothing

The Japanese word kimono means "something one wears" and they are the traditional garments of Japan. Originally, the word kimono was used for all types of clothing, but eventually, it came to refer specifically to the full-length garment also known as the naga-gi, meaning "long-wear", that is still worn today on special occasions by women, men, and children. It is often known as wafuku which means "Japanese clothes". Kimono comes in a variety of colors, styles, and sizes. Men mainly wear darker or more muted colours, while women tend to wear brighter colors and pastels, and often with complicated abstract or floral patterns. The summer kimono which are lighter are called yukata. Formal kimono are typically worn in several layers, with number of layers, visibility of layers, sleeve length, and choice of pattern dictated by social status and the occasion for which the kimono is worn.

The Japanese word kimono means "something one wears" and they are the traditional garments of Japan. Originally, the word kimono was used for all types of clothing, but eventually, it came to refer specifically to the full-length garment also known as the naga-gi, meaning "long-wear", that is still worn today on special occasions by women, men, and children. It is often known as wafuku which means "Japanese clothes". Kimono comes in a variety of colors, styles, and sizes. Men mainly wear darker or more muted colours, while women tend to wear brighter colors and pastels, and often with complicated abstract or floral patterns. The summer kimono which are lighter are called yukata. Formal kimono are typically worn in several layers, with number of layers, visibility of layers, sleeve length, and choice of pattern dictated by social status and the occasion for which the kimono is worn.

Cuisine

Through a long culinary past, the Japanese have developed a unique, sophisticated and refined cuisine. In recent years, Japanese food has become fashionable and popular in the U.S., Europe and many other areas. Dishes such as sushi, tempura, and teriyaki chicken are some of the foods that are commonly known. The healthful Japanese diet is often believed to be related to the longevity of Japanese people

Sports

In the long feudal period governed by the samurai class, some methods that were used to train warriors were developed into well-ordered martial arts, referred to collectively as Koryu. Examples include Kenjutsu, Kyudo, Sojutsu, Jujutsu and Sumo, all of which were established in the Edo period. After the rapid social change in the Meiji Restoration, some martial arts changed to modern sports, Gendai Budo. Judo was developed by Kano Jigoro, who studied some sects of Jujutsu. These sports are still widely practiced in present day Japan and other countries.

Baseball, football (soccer) and other popular western sports were imported to Japan in the Meiji period. These sports are commonly practiced in schools along with traditional martial arts.

The most popular professional sports in today's Japan are Sumo, baseball and football (soccer). In addition, many semi-professional organizations, such as volleyball, basketball and rugby union, are sponsored by private companies.

Culture of JapanThe culture of Japan has evolved greatly over millennia, from the country's prehistoric Jomon culture to its contemporary hybrid culture, which combines influences from Asia, Europe and North America. After several waves of immigration from the continent and nearby Pacific islands (see History of Japan),the inhabitants of Japan experienced a long period of relative isolation from the outside world under the Tokugawa shogunate until the arrival of "The Black Ships" and the Meiji era.Japanese languageThe Japanese language has always played a significant role in Japanese culture . The language is spoken mainly in Japan but also in some Japanese emigrant communities around the world, it is an agglutinative language and the sound inventory of Japanese is relatively small but has a lexically distinct pitch-accent system. Early Japanese is known largely on the basis of its state in the 8th century, when the three major works of old Japanese were compiled. The earliest attestation of the Japanese language is in a Chinese document from 252 A.D. It is regarded as an extremely hard language for westerners to learn as adults.Japanese is written with a combination of three scripts: hiragana which were derived from the Chinese cursive script, katakana, which were derived as a shorthand from Chinese characters, and kanji, imported from China. The Latin alphabet, romaji, is also often used in modern Japanese, especially for company names and logos, advertising, and when inputting Japanese into a computer. The Hindu-Arabic numerals are generally used for numbers, but traditional Sino-Japanese numerals are also commonplace.

. The language is spoken mainly in Japan but also in some Japanese emigrant communities around the world, it is an agglutinative language and the sound inventory of Japanese is relatively small but has a lexically distinct pitch-accent system. Early Japanese is known largely on the basis of its state in the 8th century, when the three major works of old Japanese were compiled. The earliest attestation of the Japanese language is in a Chinese document from 252 A.D. It is regarded as an extremely hard language for westerners to learn as adults.Japanese is written with a combination of three scripts: hiragana which were derived from the Chinese cursive script, katakana, which were derived as a shorthand from Chinese characters, and kanji, imported from China. The Latin alphabet, romaji, is also often used in modern Japanese, especially for company names and logos, advertising, and when inputting Japanese into a computer. The Hindu-Arabic numerals are generally used for numbers, but traditional Sino-Japanese numerals are also commonplace.

Calligraphy

The flowing, brush-drawn Japanese language lends itself to complicated calligraphy. Calligraphic art is often too esoteric for Western audiences and therefore general exposure is very limited. However in East Asian countries, the rendering of text itself is seen as a traditional artform as well as a means of conveying written information. The written work can consist of phrases, poems, stories, or even single characters. The style and format of the writing can mimic the subject matter, even to the point of texture and stroke speed. In some cases it can take over one hundred attempts to produce the desired effect of a single character but the process of creating the work is considered as much an art as the end product itself.

The flowing, brush-drawn Japanese language lends itself to complicated calligraphy. Calligraphic art is often too esoteric for Western audiences and therefore general exposure is very limited. However in East Asian countries, the rendering of text itself is seen as a traditional artform as well as a means of conveying written information. The written work can consist of phrases, poems, stories, or even single characters. The style and format of the writing can mimic the subject matter, even to the point of texture and stroke speed. In some cases it can take over one hundred attempts to produce the desired effect of a single character but the process of creating the work is considered as much an art as the end product itself.

This art form is known as ‘Shodo’ which literally means ‘the way of writing or calligraphy’ or more commonly known as ‘Shuji‘ 'learning how to write characters’

Sculpture

Traditional Japanese sculptures mainly settled on the subject of Buddhist images, such as Tathagata, Bodhisattva and Myo-o. The oldest sculpture in Japan is a wooden statue of Amitabha at the Zenko-ji temple. In the Nara period, Buddhist statues were made by the national government to boost its prestige. These examples are seen in present-day Nara and Kyoto, most notably a colossal bronze statue of the Buddha Vairocana in the Todai-ji temple.

Wood has traditionally been used as the chief material in Japan, along with the traditional Japanese architectures. Statues are often lacquered, gilded, or brightly painted, although there are little traces on the surfaces. Bronze and other metals are also used. Other materials, such as stone and pottery, have had extremely important roles in the plebeian beliefs.

Ukiyo-e

Ukiyo-e, literally "pictures of the floating world", is a genre of woodblock prints that exemplifies the characteristics of pre-Meiji Japanese art. Because these prints could be mass-produced, they were available to a wide cross-section of the Japanese populace — those not wealthy enough to afford original paintings — during their heyday, from the 17th to 20th century.

Ikebana

Ikebana is the Japanese art of flower arrangement. It has gained widespread international fame for its focus on harmony, color use, rhythm, and elegantly simple design. It is an art centered greatly on expressing the seasons, and is meant to act as a symbol to something greater than the flower itself. Traditionally when third party marriages were more prominent and practiced in Japan many Japanese women entering into a marriage did learn to take up the art of Ikebana to be a more appealing and well-rounded lady. Today Ikebana is widely practiced in Japan, as well as around the world.

The first settlers of Japan, the Jomon people (c 11000?–c 300 BC), named for the cord markings that decorated the surfaces of their clay vessels, were nomadic hunter-gatherers who later practiced organized farming and built cities with population of hundreds if not thousands. They built simple houses of wood and thatch set into shallow earthen pits to provide warmth from the soil. They crafted lavishly decorated pottery storage vessels, clay figurines called dogu, and crystal jewels.

The first settlers of Japan, the Jomon people (c 11000?–c 300 BC), named for the cord markings that decorated the surfaces of their clay vessels, were nomadic hunter-gatherers who later practiced organized farming and built cities with population of hundreds if not thousands. They built simple houses of wood and thatch set into shallow earthen pits to provide warmth from the soil. They crafted lavishly decorated pottery storage vessels, clay figurines called dogu, and crystal jewels.

by flowing dress patterns and realistic rendering, on which Chinese and Korean artistic traits were superimposed.These indigenous characteristics can be seen in early Buddhist art in Japan and some early Japanese Buddhist sculpture is now believed to have originated in Korea, particularly from Baekje, or Korean artisans who immigrated to Yamato Japan. Particularly, the semi-seated Maitreya form was adapted into a highly developed Korean style which was transmitted to Japan as evidenced by the Koryu-ji Miroku Bosatsu and the Chugu-ji Siddhartha statues. Although many historians portray Korea as a mere transmitter of Buddhism, the Three Kingdoms, and particularly Baekje, were instrumental as active agents in the introduction and formation of a Buddhist tradition in Japan in 538 or 552. They illustrate the terminal point of the Silk Road transmission of Art during the first few centuries of our era. Other examples can be found in the development of the iconography of the Japanese Fujin Wind God, the Nio guardians, and the near-Classical floral patterns in temple decorations.

by flowing dress patterns and realistic rendering, on which Chinese and Korean artistic traits were superimposed.These indigenous characteristics can be seen in early Buddhist art in Japan and some early Japanese Buddhist sculpture is now believed to have originated in Korea, particularly from Baekje, or Korean artisans who immigrated to Yamato Japan. Particularly, the semi-seated Maitreya form was adapted into a highly developed Korean style which was transmitted to Japan as evidenced by the Koryu-ji Miroku Bosatsu and the Chugu-ji Siddhartha statues. Although many historians portray Korea as a mere transmitter of Buddhism, the Three Kingdoms, and particularly Baekje, were instrumental as active agents in the introduction and formation of a Buddhist tradition in Japan in 538 or 552. They illustrate the terminal point of the Silk Road transmission of Art during the first few centuries of our era. Other examples can be found in the development of the iconography of the Japanese Fujin Wind God, the Nio guardians, and the near-Classical floral patterns in temple decorations.